There’s an easy way to reach higher notes on the violin, a technique I’ve seen it commonly used by fiddlers of older generations (and I’m getting to the age where most of those folks are gone). But it was also common for baroque violinists, for the simple reason that after the chin rest was invented in 1820, violinists began to hold the violin steady with their chin, and shift to higher positions up the neck by bending at the elbow. Of course, this is now how shifting is taught to everyone learning the violin, but there’s another way to get up there: Crawling.

When one of my violin teachers in college taught me a novel way of shifting to higher positions up the neck, I didn’t realize it was not really shifting at all. It was crawling, and it has a long and colorful history among baroque violinists and fiddlers.

That teacher was Dan Stepner, who went on to become a brilliant violinist on both baroque and modern instruments and styles. I learned a lot from him, not least of all because I believe his thesis in graduate school was about the ergonomics of violin playing.

But it was my friend, fiddler Ruthie Dornfeld, who told me one day about a book that made the connections for me between what my teacher had had me practice, how violinists had played before the advent of the chin rest, and how I’d seen many fiddlers reach for higher notes.

The book is by Ruggiero Ricci, the virtuoso violinist famous for recording all of Paganini’s Caprices, and is called Ricci on Glissando: The Shortcut to Violin Technique. A lot of the book presents exercises for practice his techniques and sharpening the ears and muscle memory, but there are some pretty interesting ideas and stories included as well.

One of the most intriguing stories is about the great Paganini, who revealed in a cryptic comment that his secret to playing the violin was that he used only one hand position.

Ricci decoded that comment to suggest that Paganini’s contact with the violin neck was his thumb, halfway up the neck, from where he would reach his fingers back to play what we now call “first position” and reach up to play in fifth or higher positions, without significantly moving the thumb.

Two cautions from me about what this sounds like: First of all, the thumb is never placed directly underneath the neck; this creates far too much temptation for the fingers and thumb to do what they do best — pinch together in order to grab something. That is powerful when picking something up, but when using the hand for anything such as playing the violin, it is cumbersome overkill, and uses far too much effort to allow for the quick touch and release, the agility and lightness, that we need when playing the notes.

The second caution, or observation, is that when the fingers move like that, sliding or crawling up or down the neck, the hand gently adjusts to the motion to make things more comfortable, without needing to deliberately shift to a new position. There is nothing rigid about the hand position, even if the anchor spot for the thumb in this technique is in the middle of the neck.

The way my college violin teacher taught it (without naming it) was by having me finger pieces of music such that I always “shifted” on the half steps. In fact, I used to practice a three-octave A scale where I never shifted at all. If you start on your 1st finger on the G string, and slide a finger up every time you come to a half step, you end up in 8th position without even trying or shedding a tear. It’s tactile and easy to hear the right note when you slide a finger up a half step, and as I said, the hand gently adjusts as you move up the neck in this way, without having to deliberately shift the whole hand or make an effort to bend at the elbow.

This kind of technique makes sense when you’re playing a baroque violin without a chin rest, though placing my thumb in the new place even while playing a baroque violin was not something I could get comfortable when I had a performance to do in a few days! It needs a little getting used to, but I think it won’t spoil anybody’s technique; it will only expand it.

I’ve seen many an older fiddler use this technique, though, and in some cases, it could come from the ease of it, or the habit in some styles of having fiddlers bend their left wrist so their palm supports the fiddle (though doing this too much can challenge the blood circulation at the wrist), or even from playing in the sitting position with the elbow on the leg supporting the hand on the neck of the violin. But the technique can also easily learned while using what I find is a more efficient and natural hand hold, with a straight wrist (as highlighted and practiced in my earlier post about the “Drumming Exercise”).

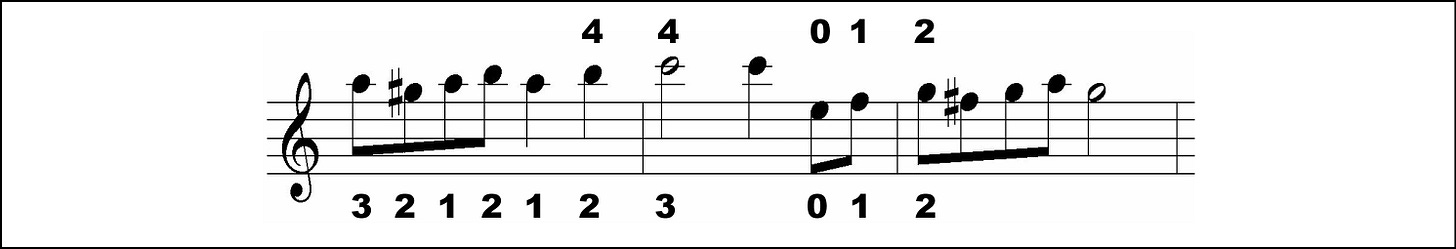

Below is an example of crawling by just sliding the finger a half step higher. The fingering above the notes shows the crawling idea; the finger below the notes shows what a violinist/fiddler might do to shift up to 3d position for this passage. This is toward the end of the Quebecois tune “Pointe Au Pic.”

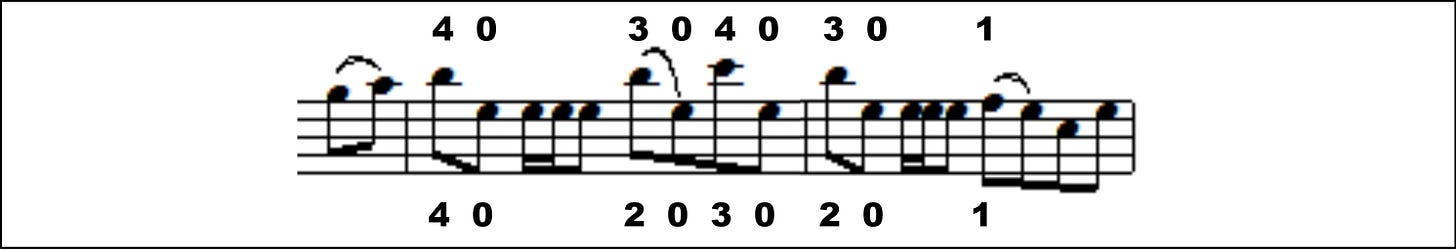

And below is part of a popular tune called “MacArthur Road” by Dave Richardson. The fingering above the notes is again based on the crawling technique. In this case, instead of shifting the hand, you just reach out the 3d finger a little higher than usual after playing the open string, and then allow the hand to adjust so you can play the 4th finger a whole step higher than the 3d. The fingering below the notes shows what many violinist/fiddlers would typically do here, mainly because when learning shifting, most students learn to shift up to 3d position as their first choice.

Well there you have it. Crawling is worth a try, worth some practice, and it’s nice to know that if you use it, it can really simplify your fingering when you need to reach higher. It’s also nice to know that you’ll be in good company, including some great fiddlers, and some great violinists like Paganini, Ricci, and Stepner!

I can't visualize this from the written description. I would love to see a video demo of it with a talking description of each step.

This is so cool. And YES, intonation better on the half step. Not mysteriously so far away.