I’d like to share how I get a student or even a class to write a tune. Usually, they don’t believe they can, and this presumption alone prevents them from trying.

Not everybody has to write tunes, or play music, or make art. And yet, when we do, it broadens our perspectives, our knowledge, our grasp of how things have come to be and what could yet come to be, makes us juxtapose ideas we never put together before, and, by the way, it grows brain cells. In countless ways, such creativity is doable, rewarding, and healthy for us and those around us.

I once talked with a great fiddler about writing tunes. He said he didn’t write any because there were enough of them out there, and it was his calling to play, not write, though he knew someone who wrote a tune a day and hid them all in a box without letting anyone see or play them. Sure enough, when that other fellow died, his boxes saw the light of day, along with thousands of tunes he’d written.

I pointed out to this fiddler, though, that his familiarity with the music could make it easy for him to diverge from a known tune and carve a new path into a tune he’d never heard before, one that others would love to hear and play. And if that’s not enticing enough, it would also give him a chance to name the tune after his wife, his daughter, his parents, his hometown, or another place or person that inspired him during his life.

One of my pandemic projects was to pull together 150 tunes that I and my family have written over the past four decades. Nearly every one had a reason for being, so we included a brief story with each tune, to flesh out the context of the tune and its title. Very often, a big part of performing concerts is setting the scene for the tunes we’re about to play, since nearly every tune has a story about how it was written, named, and how it’s been used. This knowledge of the context of a tune is also one of the cures I mentioned (in an earlier article) for stagefright.

For example, Skinner’s tune “Hector the Hero” had a very dramatic origin story (which I’ll share in my Monday Substacks at some point, based on an article I wrote previously) but the story of the tune has grown far beyond its origins. I first heard the tune performed by Buddy MacMaster, who brought it to life in a poignant way that the written version never did for me. Later I learned that he played it for his own mother’s funeral, and years later found out that it became a tune frequently requested for funerals in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. I once played it for the funeral mass of a Cape Bretoner in Boston, after reassuring a very anxious priest that I would be playing a very spiritual tune, though I left out the fact that, contrary to the priest’s request, the tune did not originate within the institution of the Catholic Church, whatever that exactly means.

And what does that exactly mean? Why are the origins of tunes so important to people? It’s not hard to understand the associations people can have with a tune that has had a history, however good or bad. We don’t have to play tunes that trigger a memory of racist uses or lyrics, since, as that famous fiddler said, there are so many tunes out there to choose from. On the other hand, we like to play a good lament at a funeral, or a contemplative slow air during a wedding ceremony, or a lively jig when the bride and groom are all hitched and can hightail it off the stage!

When faced with an upcoming or recent event, we may feel inspired to shape our feelings into a tune with that moment in mind. We just need a little understanding of how tunes are made. And that kind of understanding goes a long way. It can help us grasp the structure of any tune we like and want to learn, and therefore help us learn more quickly and retain tunes longer.

Understanding what goes into writing a tune also makes us think about the compromises composers face when putting their music on paper. Which in itself gives us pause when we get overly literal about playing exactly what’s been printed. How has the music changed between the composer’s thoughts, the translation to notes, and the transition to being printed?

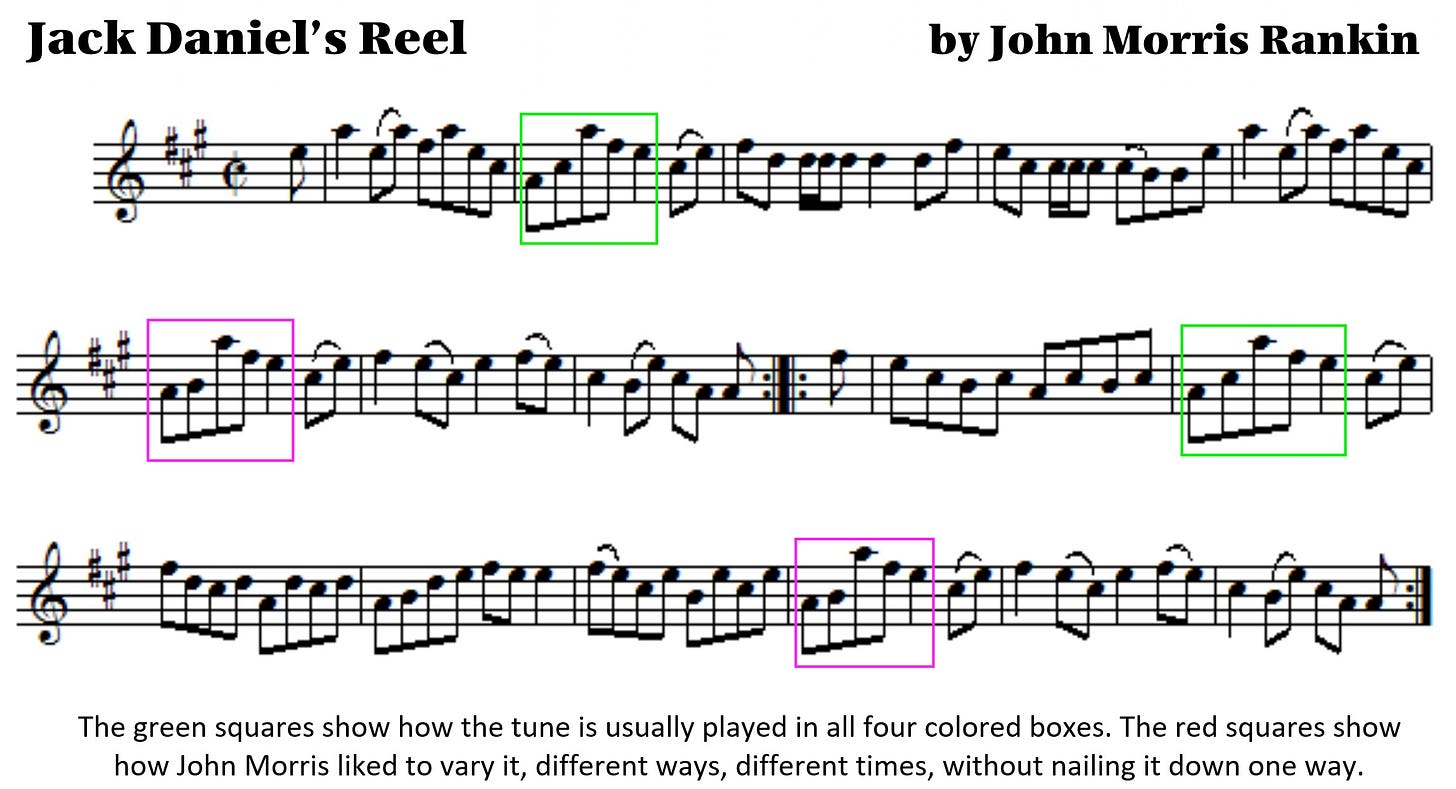

In one Scottish Fiddle Rally concert, I wanted to include a tune by John Morris Rankin, the great Cape Breton fiddler and pianist, so I spoke with him to make sure it was okay to use his tune, and to make sure we had it on paper correctly. He sent me his handwritten version of the tune, “Jack Daniel’s Reel,” in which the B part was way longer than most tunes look, since it had no repeats and had slight changes throughout. We talked about it, and for the sake of making sure a group of amateurs could play the tune, and to help fit the tune into the concert book we were going to use, we agreed to standardize one phrase that he liked to vary when he played it himself. This compromise is very common, usually for the same reasons I had — making the tune more playable, and saving space on paper. Adjustments like this can often be noticed if we listen closely to composers play their own tunes, as compared with how their tunes have been written out or printed.

I told John Morris that although we would write out the simplified version of his tune, I would pass along the message that he liked a little variety in one particular spot, something I like to do myself, in his honor, when I play the tune. Below is the tune, and the phrase that he liked to vary from time to time. It’s a small change but feels different.

Writing new tunes, whether the world seems to need them or not, or writing new stories, opinion pieces, drawing, painting, dancing — these arts are not about the end results. They are about the process of learning, exploring, facing and resolving conflicts, and we learn a lot from doing it. There was one Picasso exhibition which displayed about 150 versions he made of a Manet painting he admired and wanted to experiment with in different ways. Enough said!

As to the mental blocks about writing tunes (or learning an instrument, or making any art) that I mentioned at the beginning — the block often comes from a presumption that people don’t believe they can write a tune, or they’re not “talented” enough, etc. Daniel Levitin, in his book This is Your Brain on Music, discussed a study showing that people generally use the word “talent” retroactively — to describe people who are already accomplished. There’s a presumption that talent is somehow bred into people and naturally flowers into accomplishments, and if you ain’t got it, too bad for you. But the study showed quite simply that the people who were regarded as “talented” in a community had practiced on average twice as much as those who were not regarded as talented!

The point is, it wasn’t that it was natural to them — they worked hard, and got somewhere. There’s another message there, too, in my view. Practicing a lot suggests to some people the idea of slaving away at it, maybe because many have bad memories of some sort of forced or fear-based learning — but this kind of pressure is never a long-term motivator. If those “talented” people who practiced so much had any built-in advantage, it would simply have been that, whether from themselves, their teachers or family, they had developed an attitude toward music that included a love and joy of learning, listening, and playing. That’s what makes it possible to play (practice) a lot.

Writing a tune can be quite a joyful exercise. Since we’ve run out of space for this time, let’s dig in next week and start making a tune!