Whether making music with the voice or an instrument, the best musicians pay attention to how a musical note begins, especially if it lands on a beat. We may start it with clear articulation, a forceful bite or attack, or may start gently, cautiously. However it’s done, a note starting a beat has to placed right where it belongs. If it is begun carelessly, the music loses momentum and listeners begin to feel confused (or worse — dancers may trip, fall on their noses, and sue the musician, who may then lose everything and have to write an advice column).

Each instrument has its way of articulating the beat. On stringed instruments, it’s normally done with a change of bow direction, though it can also be done with a pulse during a bow stroke, or even by the left hand, with the flick of a grace note that interrupts the vibration of the string.

However, there are many times when a beat goes by without a change of bow, or any articulation at all. This could be because of syncopation or any note lasting longer than a beat, such as a dotted note.

That longer note carries on right through the beat — the “beat not played,” as I think of it, or maybe I should say, the beat not articulated. And yet that beat must be felt by the musician, in order to convey the beat of the tune by placing the following notes where they belong.

The beat not played causes a lot of problems for some players, especially learners. There are many who try their best to get all the notes “done” but give scant attention to those longer notes that cross over the beat. These single, longer notes seem easy to play, and less challenging than places in a tune where there are more notes, especially the fast ones that take up lots of ink on the page! The irony is that a single long note, which seems easy to play, may cause someone to take the beat for granted and derail the whole tune. And if you don’t keep a good beat, it’s very difficult to play along with others. (Not to mention the problem pointed out above, about dancers and their noses.)

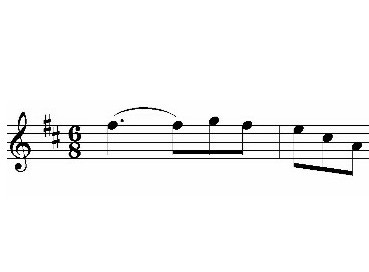

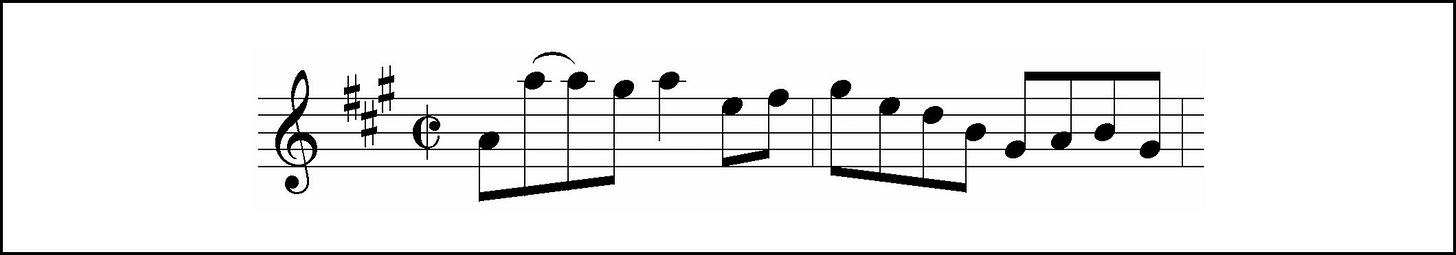

Here is the beginning of the slow air “Da Slockit Light”:

The open D starts on beat 1, and is held through beat 2. The next note is played just before beat 3. If you think only about getting all those notes played and out of the way, you might not hold the D long enough, and the timing of the tune will not make sense. We have to hear the A exactly on beat 3, or the tune will get off to a confusing start.

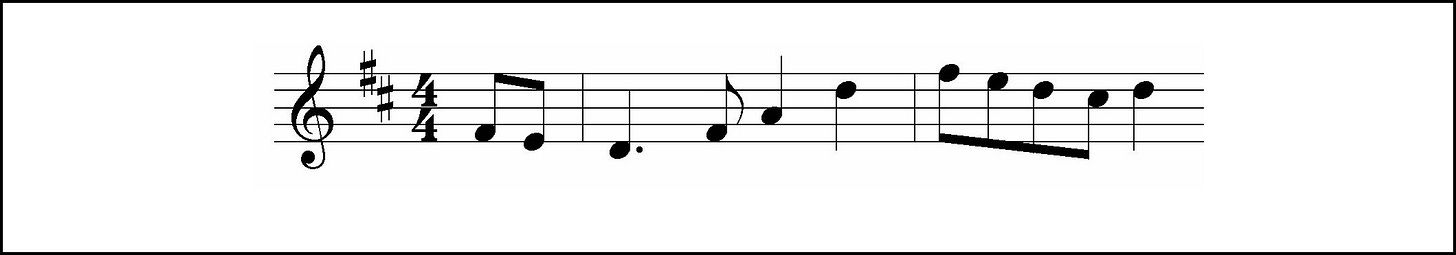

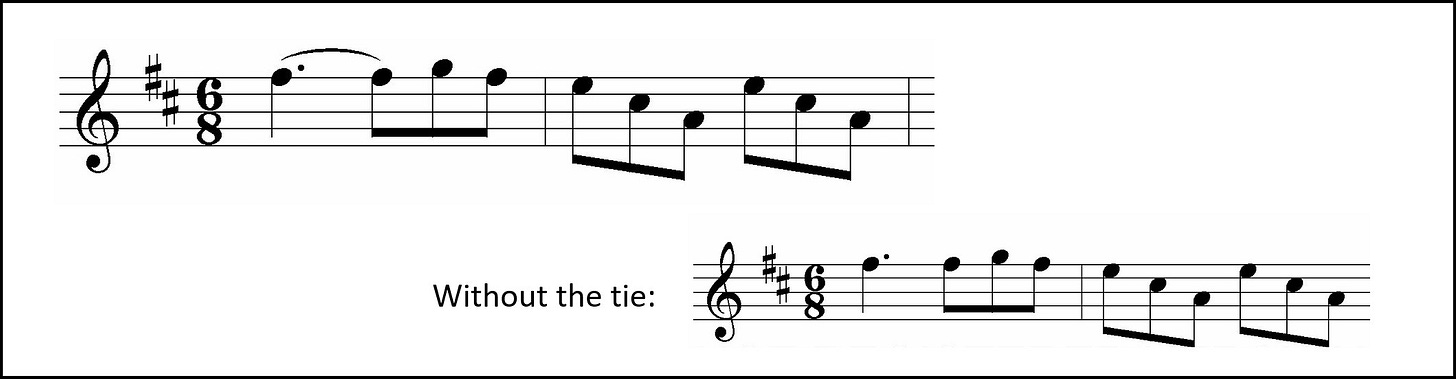

Here’s another way to write the same timing:

The dotted quarter has become a quarter note tied to an eighth note. This is played exactly the same as in the previous example, but by writing out these two notes tied together, the beat note becomes visible, instead of being part of the dotted note.

When it’s written or thought of this way, we can also easily take out that tie altogether, and play the two D’s separately. This forces us to reserve time for the beat note, so we won’t skimp on it. If you ever have trouble with the timing on dotted notes such as this, go ahead and play the note again on the beat. After you feel comfortable with this timing, it’s not hard to put the tie back in, as long as you make sure you continue to feel the beat the same as you did when you played the two notes separately, without the tie.

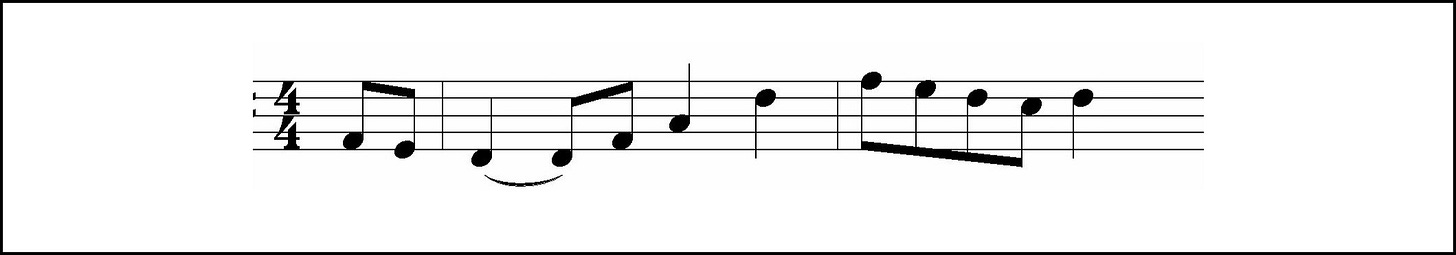

These observations apply also to syncopated rhythms, as in the start of “Sleep Soond Ida Moarnin”:

In the old days, this Shetland tune was written with a tie, like this:

When playing this tune, some players think about the tie and give the bow a push to emphasize the second note in the tie. As with the other tune, you can choose to take the tie out and play four eighth notes to start the tune, or leave the tie in and pulse the bow in order to hear the second tied note. However you play it, try to feel that second note of the tie, in order to reserve time for it and keep the beat clear.

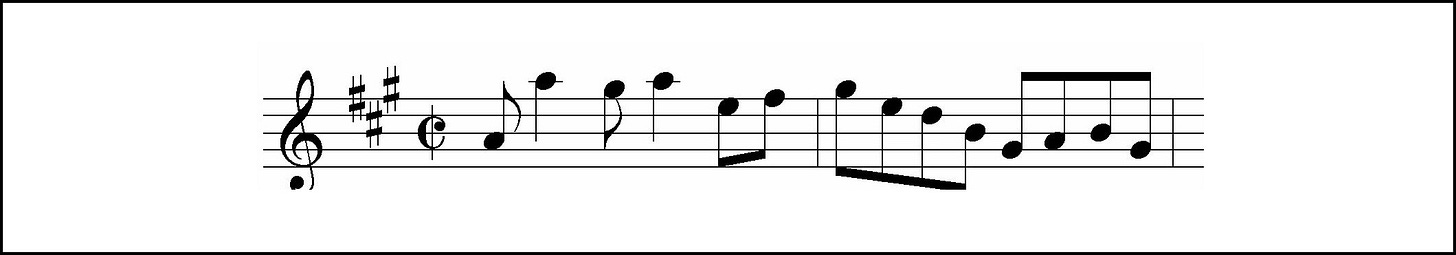

Here’s one more example of “the beat not played,” from the beginning of the jig, “Fair Jenny”:

In this case, we hold the first note for a full beat (dotted quarter in jig time), plus one more eighth note on the same bow, before playing the rest of the triplet. We must feel that second beat strongly even if we’re not changing bow on it. Again, if there’s any uncertainty about this, cut out the tie and play the second beat note separately as the start of a triplet. This will emphasize the beats (and keep the dancers happy!). It’s also a perfectly fine way to play the tune. When you’re comfortable with the timing, the tie can be used as a variation. It’s fun to keep the bow going on that second note, but only if you feel the second beat clearly. You can even give that tied note a pulse by digging in with the index finger of your bow hand.

If you have any trouble keeping the beat when playing tied notes, it means you weren’t feeling the beat. In the “Fair Jenny” jig, taking out the tie helps you feel the beat and get it across to listeners. And don’t forget that the second beat is filled with a triplet. You have to get right off the beat note onto the other two eighths so you can land on the next beat on time at the beginning of the following measure. And then on to the next beat, and the next. No rest for the wicked, or the weary, or the fiddler!

Remember: Music is not a to-do list; it’s an appointment calendar. You have to get to your appointments (with the beat notes) on time; it doesn’t count if you just get all the notes done.

Be sure to feel the beat even if you don’t change bow on it. Beat notes are the structure of the tune; the notes in between are just decoration!