Reading Music Fluently

A different take on reading, for all levels and music teachers

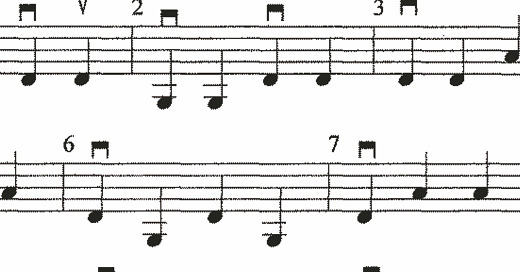

This and the next couple of posts are for all levels of string player, and music teachers as well. It will help beginners or anyone who hasn’t learned to read music fluently, and offers new takes on how to think about reading, and (esp. next time) about note patterns such as arpeggios.

I don’t teach the reading of music as if teaching the reading of word…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Essays On Music & Learning Fiddle/Violin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.