If someone you know would enjoy these articles about learning fiddle and other musical musings, please consider giving a gift subscription!

Because of an upcoming concert, I’ve been getting used to playing a baroque violin, and it takes quite a few adjustments to my playing technique because of differences in the strings, bow, and chinrest.

I’ve decided to play Scottish music on two Scottish violins, one made in 1774, the other in 1923 (now celebrating its hundredth birthday). Our program features 18th-century Scottish music played on the baroque violin, and early 20th-century Scottish music on the centenarian violin. Today we’ll focus on the baroque violin and how I’m adapting to playing it.

I will say briefly that the 1923 violin has quite a story of its own. Its maker, Alexander Hume, was forced to leave Scotland during World War I due to scandals of his own making. His son Jock was one of the three crew violinists who went down with the Titanic in 1912, but Hume refused to acknowledge his son’s wife or baby (not approving of their station in life), and his daughter wrote a tirade against him which landed her in a horrible prison, thanks to her own father’s lawsuit. Nevertheless, he was a great violinmaker! I remember several appraisers being puzzled by the 1923 violin because the label said “London” but they felt it was of much better quality than the average English violin of the time. Not until 2013 did I find out that the maker wasn’t English at all, but had fled there from Scotland only a few years before making the violin. The full story of that violinmaker’s family can be learned from And the Band Played On, by Jock’s grandson, Christopher Ward, about the fascinating aftermath of the sinking of the Titanic.

The baroque violin was made in Aberdeen during the Scottish Enlightenment, a time when that city took over from Edinburgh as the center of fine Scottish violinmaking. In the following generation that honor gravitated to makers in Glasgow. Although Scotland has had more violinmakers per capita than any other country, and has produced excellent instruments, most violin shops still pay Scotland scant attention (and probably underprice the instruments as well!).

I’m not an expert in playing a baroque violin, though I’ve been around them for a long time (my brother directs a baroque orchestra). But the differences are fascinating. The bow is slightly shorter and lighter, with fewer hairs. The D, A, and E strings are pure gut; mine came in double lengths, so I had to cut them in half, and tie a knot in one end to anchor them in the tailpiece. The G string is gut wrapped in metal, much the way many modern strings are, though most players now use synthetic gut. The synthetic imitates the warm sound of gut but is made from a type of nylon that is more durable and stays in tune longer. Wrapping the G string in metal helps protect the string but also increases its mass, so it can sound lower while being no thicker than the other strings.

Gut strings are very responsive, but are under less pressure than metal strings, and are generally quieter. Most baroque violins have necks that stretch straight back from the bridge, whereas modern violins have necks that tilt back in order to accommodate the extra pressure of the strings. (It’s less of a strain to pull on a rope if you lean back from it than if you’re standing upright.) Many baroque violins had their straight necks replaced in the 1800s, in order to tilt them back, so they could handle modern strings. The neck of my baroque violin is a little different, though, because it was originally made with that tilt, not for the sake of the pressure of the strings, but to clear the high arch carved into the body of the violin.

Gut strings easily produce a nice bite to the notes, which makes them fun for playing the old dance tunes. But these strings are also more temperamental than modern strings, and I find I have to use different pressure and more bow on each stroke than I’m used to.

There’s no chin rest on baroque violins; this gadget was invented by Louis Spohr in 1820. By using the chin rest, violinists can more easily hold the violin with chin or jaw, and shift the hand up and down the neck from the elbow. There is some evidence that prior to that, violinists held the violin with the hand, even possibly leaving the thumb halfway up the neck and shift the fingers up and back as needed. Paganini suggested that his secret to playing his fiery violin pieces ranging up and down the neck was that he used one hand position, anchored by the thumb, with fingers flying up and down from there. Many old-style fiddlers use this technique as well, moving up to higher notes with their fingers rather than moving their hand. This requires an ability to crawl rather than shift to higher and lower notes, which generally means sliding up and down on half-steps where possible. If you play a G scale and only slide up on half-steps, you will end up in 5th position on the E string, so it’s an interesting and useful technique for moving up and down the neck. The great violinist Ruggiero Ricci developed a whole “glissando” technique based on these ideas and wrote a book to describe it, with many exercises to practice playing this way.

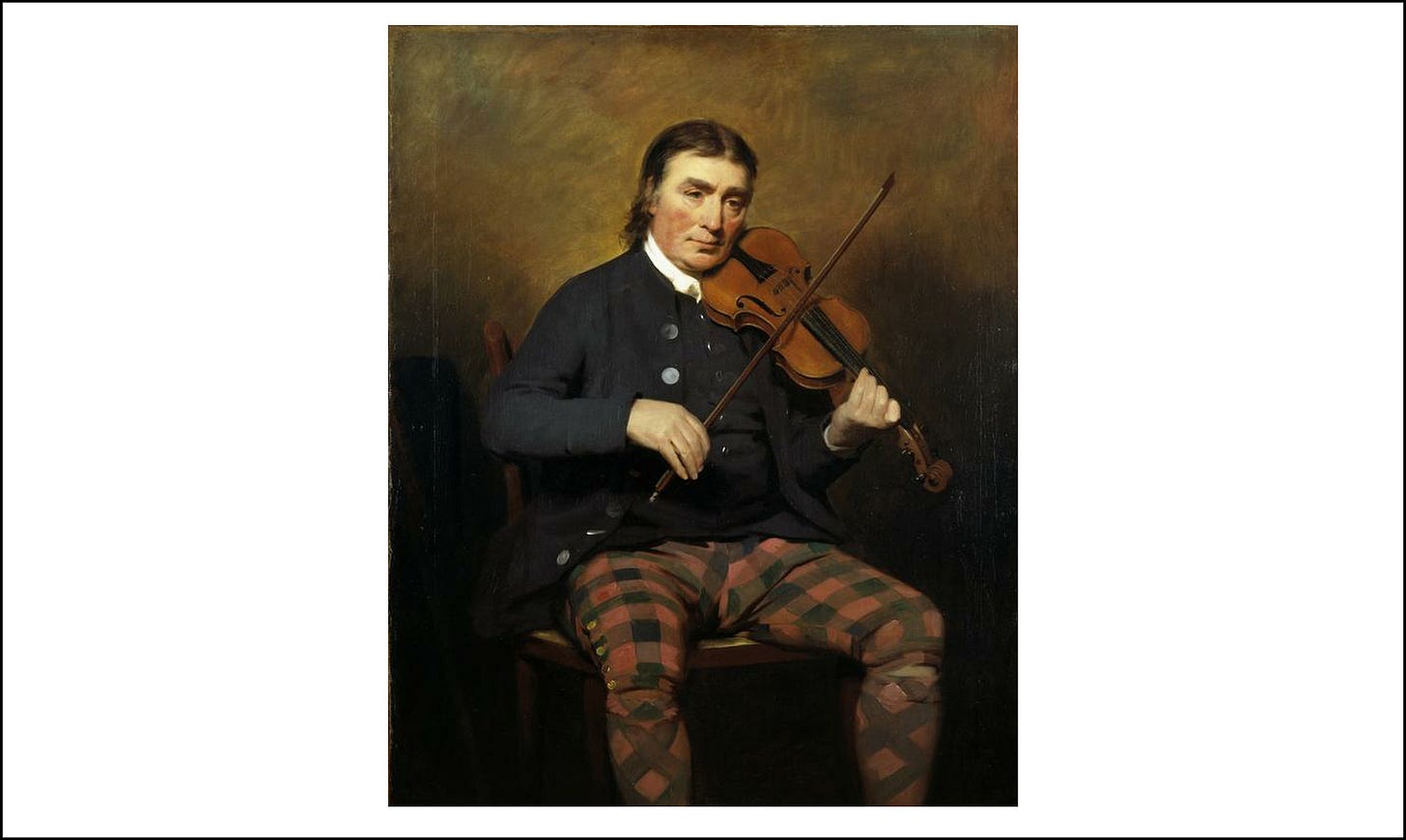

Before the chin rest was in use, people held the instrument differently. Nowadays, I often see baroque violinists place their chins roughly on the tailpiece, as if there was a central chin rest. In the old days, according to paintings, players held the instrument in various ways, some tilting it partly sideways and resting it on their upper chest. I’ve known some fiddlers who do this in order to sing or call a dance while playing.

A famous painting of 18th-century Scottish fiddler Niel Gow shows him resting his chin on the side of the violin opposite where modern chin rests are usually placed. I find that doing this keeps the violin from sliding down my chest, so it makes a lot of sense. However, it also places my left ear closer to the instrument than I’m used to, and I’m even considering using a musician’s earplug to protect it!

The gut material used to make the old strings is sometimes called “catgut,” which has given rise to the saying that playing the violin involves rubbing the tail of a horse on the gut of a cat! But the term catgut is an abbreviation for “cattle gut” — cat lovers will be happy to hear that cats don’t have enough intestine to make a string. Traditional strings were made with either sheep or beef gut.

For the upcoming concert, I don’t have the time to really adjust my playing style, so I will be using the anachronistic shoulder rest to help me hold the violin up. But I’m also using Niel Gow’s trick of placing my chin to the right of the tailpiece. It’s interesting to practice some old familiar tunes on an unfamiliar instrument. My use of gut strings and baroque bow require a different bow speeds, pressures and energy than I’m used to.

But it is rewarding to play 18th-century tunes on a contemporary instrument. At a time when continental aristocrats were patronizing the likes of Mozart and Haydn, Scottish aristocrats were patronizing their own native composers, such as Niel Gow and William Marshall. Their tunes certainly give the violin a run for its money. Some folk even complained to Marshall that his tunes were too difficult. He replied, “I don’t write music for bunglers!” Don’t worry, Willie, I don’t plan on bungling your tunes in the concert! They are some of my favorites.