Last week, we talked about recent research on dyslexia and how it is linked to rhythm. In that article, Professor Goswami of the University of Cambridge suggested that one of the key factors in understanding speech is how we sense the “rising energy” leading into emphasized syllables.

This is exactly why pickup notes are so important in music. They lead us into the beat notes, just as, when we talk, the rising energy in our voice points the listener to the important words. A computer voice saying “You. Had. Better. Go.” will not convey urgency and often, very little sense, because we tune in so much to the tones and rhythms when someone speaks. It would be much clearer to hear “YOU had betTER GO!!” where “betTER” is my attempt to convey how our voice rises through “better” into “GO,” making people really listen to that most important word of the sentence.

Pickup notes perform the same job in music. They are perhaps easiest to notice when they introduce a tune. Often there is a note or two leading into the first beat note of a tune. These pickup notes are written before the first bar line, and prepare us for the timing and tempo of the tune. But as we’ll see, pickup notes can really be found everywhere, and our awareness of them determines the musicality of our playing.

Often when I teach tunes, I mark out phrases, as on fiddle-online interactive sheet music (here’s a sample), where I’ve drawn a colorful box around each phrase. I do this for several reasons — first, these boxes allow us to learn manageable building blocks of a tune and understand how a tune is put together, and second, they include pickup notes as part of the phrases. Without these markings, written music only shows us where the beats are, but not where the phrases are. The phrases are integral to learning, retaining, and understanding music.

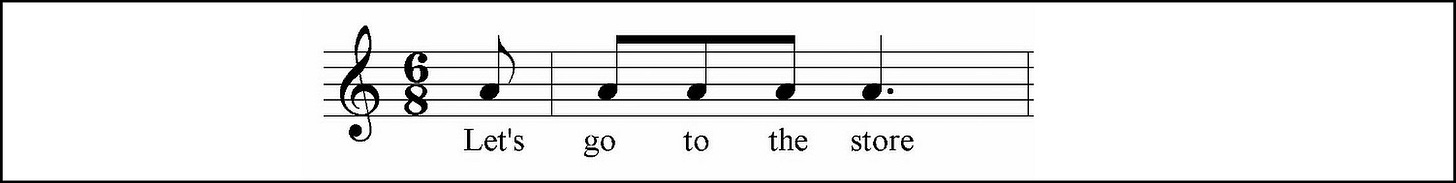

We can better understand the role of pickup notes if we keep in mind this connection between the language of music and that of singing and speaking. The two strong beats in the sentence, “Let’s go to the store” are “go” and “store”. These tell us the main idea, while the other words add nuance. The syllables before those two main words are like pickup notes leading into beats — “Let’s” belongs to “go”, and “to the” belongs to “store”. In music this sentence might be written in jig time:

If we were to split up these words by beat (as in the written music), we’d be saying it like this: “Lets. Go to the. Store.” This doesn’t make immediate sense in words or music. In order to play naturally, more like the way we speak, we need to include the pickup notes that precede each beat note. We say “Let’s go” followed by “to the store”.

Pickups prepare us to listen to the beat. I like to cite the example of a performer leaping onto stage and saying “ta-DAH! Here I am!” If she just said “DAH! Here I am!” the effect would be much weaker. The pickup “ta” prepares us to get excited for the “DAH.”

Pickups are important connectors. In a tune, the melody is constructed from a sequence of beat notes, and the nonbeat notes create a pathway between the beat notes. Nonbeat notes, including pickup notes, are changeable, even expendable, without losing the melody. To play a particular tune, we have to pass through all the beat notes.

Remember that when learning tunes, the first beat note is the first note of the first full measure. The first note of a tune is not really the pickup note or notes — these might be eliminated or changed as needed, especially when fitting together several tunes in a row. In speech, this type of thing can happen to connecting words such as “and”, “but”, “if”, and “when,” which are certainly helpful to the flow of meaning but are changeable as needed. In the example above, “Let’s go to the store,” the essence of the idea is “Go … store.” Connecting those two words with “to the,” as in “Go to the store,” allows the idea to flow. A pickup could also be added before the word “go” to change the mood — it could be “let’s” or “I’ll” or “you,” or nothing at all, depending on whether it’s an order or a suggestion.

We always emphasize the beat note more than the pickup notes, or other nonbeat notes. But the pickup notes serve an important function, like the “ta” before the “DAH”, the “rising energy” that alerts us to a coming emphasis or beat. So we want to use them to pave the way to the beat

To connect pickup notes to the beats on the fiddle, we usually play the pickup note(s) on an upbow, so we can lead into a strong downbow for the beat note. It makes a huge difference if the sound of our bow on those pickup notes grows into the beat. (We’ll explore how to do this in playing reels and jigs, in future articles.) Try to make the sound of your bow connect and grow into a beat note, to add energy during the pickup notes as you take us to the next beat. Avoid being too literal about written music, which visually separates the notes of one measure from those of the next.

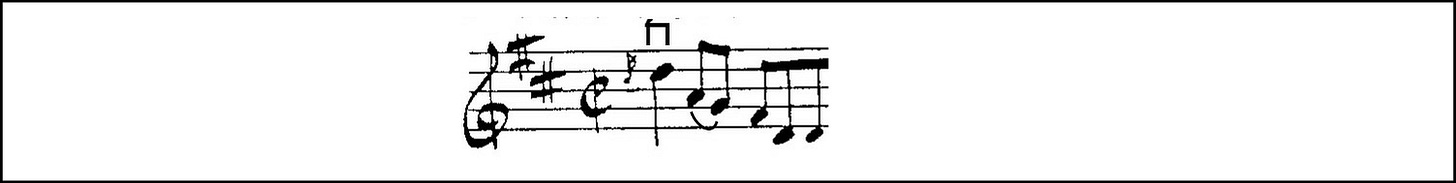

Let’s look at the A part of the reel “Miss Rattray”—

Here’s the first musical idea:

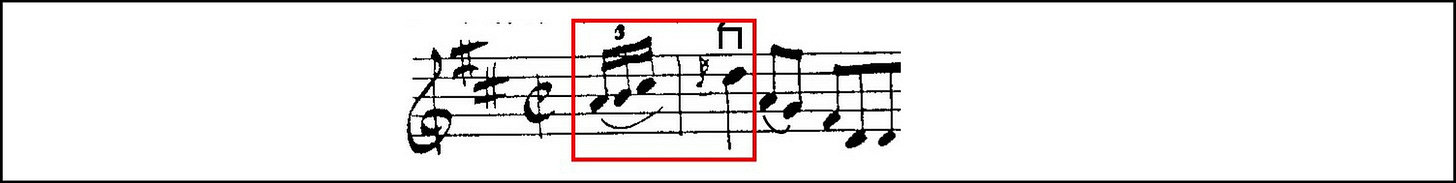

Note that there’s an eighth note missing at the end of the example above. That’s because the target note of this measure is the beat note (F#) followed (like an afterthought) by the two Ds. The missing note that follows the Ds is really just a pickup that will lead us into the next beat. This concept, that the final eighth note belongs to the following measure, is not indicated in written music. But if you can play through the eighth notes of a reel while being aware of the pickup notes leading into each beat, you can propel the tune forward and give it “lift.” This is what makes people want to tap their toes and dance to your playing.

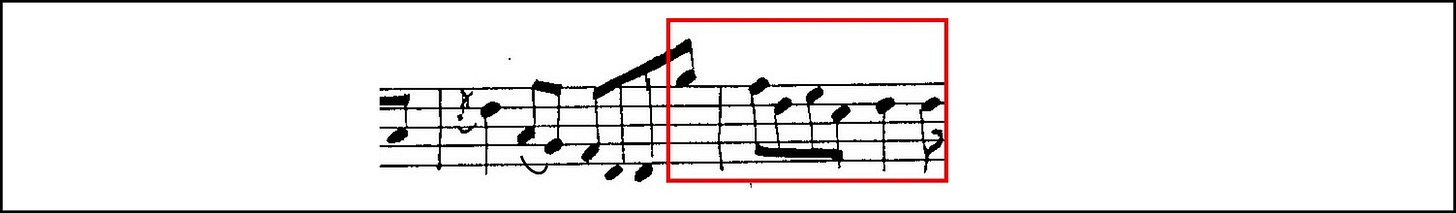

Ok this time, there are pickups (see below) that lead into the initial idea of the tune. Our sound should grow from the open A into the first beat note, the D. By the way, it’s not helpful to imagine (or memorize) that this tune starts on an A note. That’s merely the pickup. The tune really begins on the D at the beginning of the first full measure.

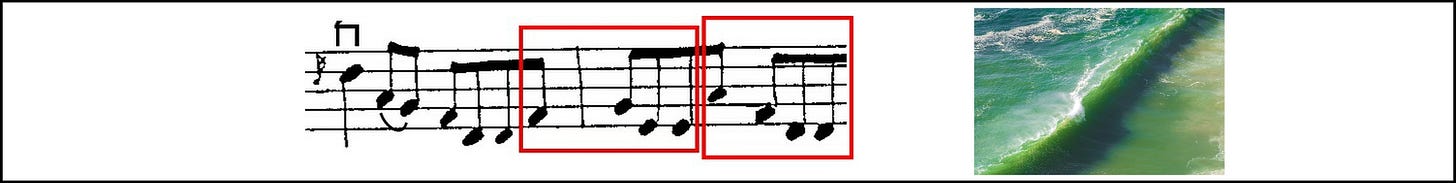

Notice how the red boxes (in examples above and below) include the pickup notes. Thinking in this way makes a tune come alive, always leading the listener into the next beat.

I like to think of the beat as the crest of an ocean wave, and the following nonbeat notes as the water gathering itself toward the next crest. Beats of music do not sit in a vacuum; they lead from one to the next, like ocean waves.

The second phrase (below) of the tune is not only difficult but fairly nonsensical if we try to learn the four notes of the second beat together, because of that huge leap across two strings in the middle:

But if we think of the last note of the first measure as simply a pickup belonging to the second measure, it’s much easier to play, and much easier for the listener or dance to hear what we’re doing.

Pickups can be found everywhere. A jig measure (in 6/8), with a quarter note followed by eighth, will sound better if the eighth note leads into the following beat note. In reels, we often run across a quarter note followed by two eighth notes. Those eighth notes sound good when thought of as pickups leading to the next beat, and are best played on an upbow leading to a downbow emphasizing the beat note.

There’s a mind shift involved in switching the allegiance of pickup notes from the measure they may be written into, to the beat note that follows. For example, those two eighth notes following the quarter note don’t belong to the quarter note, as it may appear in written music. The pickups belong to the beat note that follows them. It may seem subtle to make this mental shift, because you still want to play all the notes in time, but it makes all the difference in the feel of the tune, the logic of the bowing, the lift of the playing.

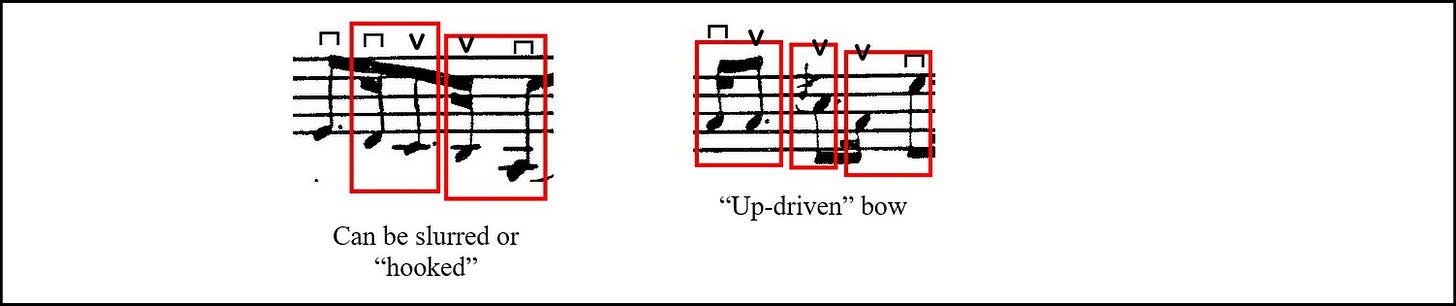

Those who puzzle over strathspeys would do well to notice how in the typical strathspey rhythm, the sixteenths are really pickups leading to the next beat, except where there’s a “snap” rhythm (sixteenth note played on the beat, as when saying the word FID-dle). Below are some examples of special strathspey bowings. The first is the most common strathspey rhythm, and can be bowed DOWN, down-UP, up-DOWN. The second is a special effect called the “up-driven bow.” I've seen it often described as one downbow and three ups, but as you can see, it’s really DOWN-up, UP, up-DOWN. Each box represents a musical idea, whether a pickup leading into a beat note, or a beat note on its own. In the case of the “snap” (first red box of the “up-driven bow” example), the short note is the beat note and uses as much bow as the longer second note.

How we sound depends a great deal on whether we are thinking ahead and moving the music forward by leading our pickup notes into the beat that follows, or thinking in a static way by tacking the pickup note onto the end of the previous beat. Think toward the next beat, and take your listener there, rather than dwell on the notes you happen to be playing at the moment.

Just as in effective singing or speaking, the “rising energy” of pickup notes in music allows us to move the music forward, and tell a musical story. We all have one to tell, in each tune we play.