I want to wish you a warm and friendly holiday season! I’ll be taking a break and will resume these articles in January. Your comments, suggestions, requests, observations, are always welcome, whether by email reply or by leaving a comment below.

If you’re looking for holiday gifts, you might like to check out my online store, where you can find a tunebook, CDs, and gift certificates for using fiddle-online.com, my 10 year-old website which embodies in a hands-on way much of what I write about in these columns.

Of course, another great gift would be to give a gift subscription to this column — in doing so, you’ll both support my work here and give lots of ideas about music and learning fiddle to someone who you think would benefit from reading these articles. Until the new year!

I sent my “Dyslexia and Music” article to a student who is a good musician and said he himself has struggled with some dyslexia over the years. The article highlights some of the fascinating connections that researchers are finally making between dyslexia and the processing of music in our brains. Dyslexia appears to be more of an input problem tied closely to audio perception, rather than a visual perception or an output problem that shows up when writing words. And not only have researchers not found any effect of dyslexia on the playing of music or singing, it appears that these skills are linked to different parts of the brain.

Some years ago, I came up with a saying about music and words that I’ve found to be a useful reminder: “The only place where music and words really meet is in song.” As a teacher and writer, I’ve been very aware that verbal descriptions of how music is heard, played and learned never really match up very well with the acts of hearing, playing and learning music. Words (much like written music) can only approximate what’s going on. For myself, in a broader sense, I connect this idea to a deeper thought, which is that “all truths are nonverbal.” Words — however apt, poetic, instructive, accurate, or even sacred — can never do more than approximate what they describe. For this reason, learning to play music, and listening to it, or attempting any art, writing or design, necessarily reaches into a part of ourselves that our words, thoughts, and logic can never fully grasp. This may be why they say that learning an instrument (and probably learning any art) actually grows brain cells.

My student liked my article connecting music and dyslexia, and responded by sending me the video I’ve included at the end of this article. It shows several moments in the recovery of Gabby Giffords, the U.S. representative from Arizona, who was shot in the head in a 2011 assassination attempt, during a mass shooting at one of her constituent events near Tucson. Since then, she has spearheaded a group fighting for gun control.

Giffords was shot in the left side of the head, which is where the language center is located. She received speech therapy and music therapy, and has managed to recover her powers of speech and some of the vivacity of her personality.

One of the more poignant moments in the video below is when, after a speech therapist tries unsuccessfully to get her to say the word “light,” she is encouraged to sing the song “This little light of mine, I’m going to make it shine,” and has no trouble singing the words, including the word “light.”

How can this be? It appears that the language center is located on the left side of the brain, but music uses all parts of the brain. I remember working with a great Scottish singer who has a rich, expressive voice and flawless diction, who, much to my surprise, has a strong stutter when speaking. When he’s singing, that stutter never appears.

Researchers believe it is even possible to use music to rebuild and relocate a damaged language center — normally, as I mentioned, located on the left side — to the right side of the brain. The Dyslexia article points out that one of the new treatments of this disability is to use singing, especially songs based on nursery rhymes, because they have very strong musical beats that reinforce the syllables we emphasize when speaking.

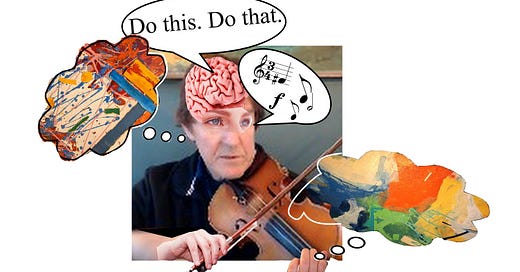

As I teach music to students, I frequently run into the struggle people have with logical and verbal thinking that sometimes blocks them from being receptive to the listening and muscle memory skills that make it possible to play an instrument. The eyes and the brain, which we rely on all the time to take us through our day, take up a lot of bandwidth that takes attention away from what the ears and fingers are trying to do when playing music.

Our language center of the brain is often at a loss to verbalize what is going on. This may be because we generally think about things we can verbalize, which in music includes the notes and other markings showing up on written music, or verbal descriptions of bowings or exercises. And yet, so much of what we’re actually doing and learning is nonverbal. Many’s the time I’ve watched a student place her bow and fingers on the correct string, ready to play the next note, and then look up at me and say, “I don’t know what to do.” In that situation, I often say, “Just play. Move the bow. See what happens.” And they often find themselves playing the tune, in spite of “not knowing what to do”!

Down the road, I’ll be talking a little more about how modern cognitive science has veered toward the primacy of bodily signals, and away from the notion that our brain is the CEO in the executive decision center, making everything happen. This ties in closely with how we learn, play, and listen to music.

In the meantime, here’s that thought-provoking video from ABC News of Gabby Giffords relearning how to speak.