Note that the video at the end of this post is also available on fiddle-online — the technique videos there take you through many of the exercises described in these posts.

~ You’re welcome to subscribe for free to get these weekly posts in your inbox! If you get something out of them and would like to support me in writing these, the best way is to donate the equivalent of 1/5 of a fiddle lesson a month for a paid subscription! Many thanks.

The fiddle/violin game I’d like to share today is simple, physical, and for that reason, easy and effective.

I call it “Long Bows.” As a warmup, it’s a perfect transition and buffer between music and the workaday world. I’ll explain why in a minute.

Place your bow on the G string near the frog (but not under your hand). Take a moment to place the bow where you want it — on the string, near the D string, halfway between the bridge and fingerboard. Once you do that, it’s best to focus on ears and hands, and not look at your bow at all. Maybe look out the window while you do this, and see if a bird flies by. The great violinist Itzchak Perlman once said he liked to practice while watching TV with the sound off! (I seem to recall he would watch a sports game that way, but if you come across this quote, leave a comment and let me know, thanks!)

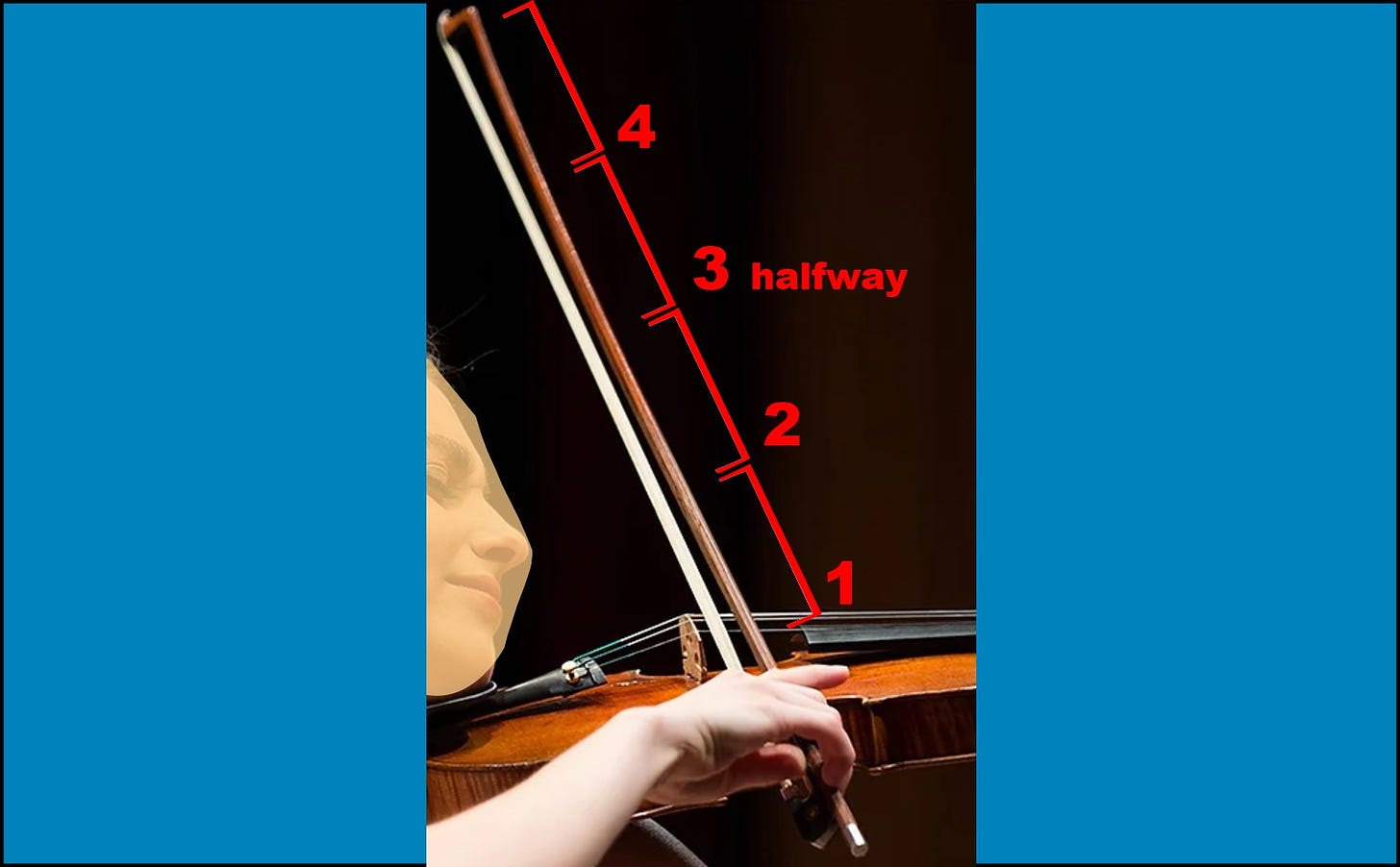

Before you start moving the bow, count to four — one second per count is a nice tempo. Then keep counting as you draw the bow on the G string. After 4 beats, switch to an upbow on beat 1, and bow upbow for another 4 counts. Switch again to downbow — 4 bows per string gives you a nice chance to get into this exercise. It also gives you only one chance to bow from up to down on each string.

When you get through the fourth bow, roll the bow smoothly to the next string as you switch to the downbow on the new string and start again with 4 bows, 4 counts each. At one second per count, on all four strings, this will take a total of one minute.

I describe all of this in what may seem like obvious detail because a bunch of things are happening that are worth being aware of. First, consider that music counts from the start of each beat, unlike, for example, rulers or birthdays, which count “1” after you’ve measured an inch, or after you’ve lived a whole year.

This means that when you get to beat 3 you are halfway through your 4 counts, and when you get to beat 1, you’re starting again in the other direction. Can you choose a bow speed that gets you halfway through the bow by beat 3? If not, try on the next downbow. Wherever your bow gets to at the end of beat 4, you need to switch to an upbow. The game is to see if this can be at the very end of the bow. If you get to the end of the bow early, you have to wait for beat 1 before starting your upbow. Time is in charge here.

Beat 1 is not a moment — it’s not a metronome click. It’s the whole time period from when you say “1” until you count “2.” Fill that time with beautiful sound. Aim for a good sound in every part of the bow, or at least take notice of what kind of sound you get in each part of the bow; your sound is likely to change unless you stay on top of it. If you just start the bow and go without paying attention to your changes in sound, it’s kind of like driving on a road and not noticing that there are curves and bumps.

A good sound depends on the ratio of bow speed and pressure. In this game, keep your speed consistent, so you can fill the whole bow in 4 counts. That leaves just your bow pressure to decide whether you sound good or not. If you’re near the frog, there’s already a lot of pressure from the weight of the bow alone, so you can’t add too much with your pointer finger, and might even need to remove some pressure using your pinky. But when you get to the tip of the bow, there’s no bow weight at all, so all of the necessary pressure to make a good sound in that part of the bow comes from your index finger (pointer).

Okay, I lied a little, sorta kinda. Pressure isn’t the only factor in making a good sound once you maintain a steady bow speed. The distance of your bow hairs from the bridge also has a big effect on your sound. Close to the bridge, you’ll need more pressure and closer to the fingerboard, less. But as we said at the beginning, the goal here is to stay halfway between the bridge and fingerboard. I also said not to look, because your eyes are at a weird, foreshortened angle, and they’re farther apart than your strings, so they don’t really help very much, especially if you make them go crosseyed. Most important of all, though, you really want to develop your skills using your muscle memory and your ears (not your eyes). You can hear if the bow drifts toward the bridge — your sound will get wispy; and if it drifts toward the fingerboard, the sound will get scratchy. If these things do happen, it means your bow isn’t straight. Take another look at the Triangle and the Body Mapping to help keep your bow straight. We’ll also talk more about this in other posts later on.

The Long Bows are a great warmup because they get your strings speaking without you having to choose a tune to play or worry about any left hand shenanigans. Just use it to make a good sound for a whole minute, and to get a sense of the entire bow and what it needs you to do to sound good, to bow, and above all, keep in good time.

Feeling four counts per bow is handy because so much fiddle music is based in fours, usually four beats in a phrase (2 measures) or in some tunes like strathspeys, four beats in a measure. But you could benefit from counting 3 or 5 or 34 if you really want to, as long as you’re consistent.

Focusing on your timing is the best buffer between the workaday world and music, because most of our worldly tasks are about getting stuff done and checking it off, whereas music is about time. You can’t just get a beat done and checked off. You have to fill it with sound, and move into a new one. After each bow of 4 beats in the Long Bows, you change direction of the bow and play another 4 beats and if you do it right, there is no hesitation — the sound will be continuous. The same is true when after 4 bows, you roll on to the next string, because your bow never stops.

Don’t forget: Breathe. Your bow breathes with those beats, and you can, too. Those pesky to-do lists out there in the regular world couldn’t care less if you catch your breath, as long as you keep busy! Not in music. Everything in music, even a simple game like “Long Bows,” is about filling and enjoying every moment with sound, and moving on to the next beat on time. Some of the relationships in music are between pitches — getting them in tune and such -- but the most important relationships in music are in time, from beat to beat, phrase to phrase. It’s the same as when we talk — instead of just spouting out the sounds of letters or words, we like to have something to say, in phrases and whole thoughts. And when we mean what we say, we say it with excellent timing. In music as in talking, when a musician has something to say, it comes across with good timing.

Long Bows sets you up for good timing and good sound, via a super easy warmup.

About the Video below

This video takes you through the game/exercise described above, illustating it and reminding you as you go about how best to approach it. Out of respect for those who pay a small fee to access it on fiddle-online.com, and out of appreciation for paid subscribers here, this video is only available to paid subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Learning Fiddle & Other Musical Musings to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.