Last week, we talked about why we all can and should write some of our own tunes. Let’s get specific about one way to actually write one, whether on your own or with others.

But first, it might be helpful to summarize why it’s great to make up tunes!

It's fun.

It's easier than you think (see below).

You get a better sense of how tunes are constructed, by phrase and part.

You learn about why tunes are written down the way they are, and why there's always more to a tune than can be written.

You learn about how music is written down, which is often a surprise even if you’ve read music all your life!

You get to name your tunes after somebody or something important to you, or just a fun title for others to get a kick out of.

And let’s acknowledge the elephant in the room — some of the best tunes may come to us in a flash of inspiration: the moment we hear of a momentous event, or a time when we notice ourselves humming a tune we’ve never heard before as we walk somewhere captivating, or after we’ve experienced a change in mood, or a fresh take on things. The trick is to hang onto such tune or motifs, to value them as ideas worth shaping into full-fledged tunes or songs, and preserve them by recording or writing them down.

If an idea comes to you that you like, and it’s just a phrase, or a small piece of a melody, hang onto it and use the steps below to work with it. Singing it just three times is often enough to fix it in your ears.

Step 1: Choosing a Few Notes

Pick five or six random notes by playing them on your instrument or singing. Play them the same way three times, and you’ve got something!

Sometimes I’ll have a class write a tune together. I might ask for someone to volunteer a few notes, but often, I’ll just pick one student out and ask them to supply us with four or five random notes. It’s pretty low-risk!

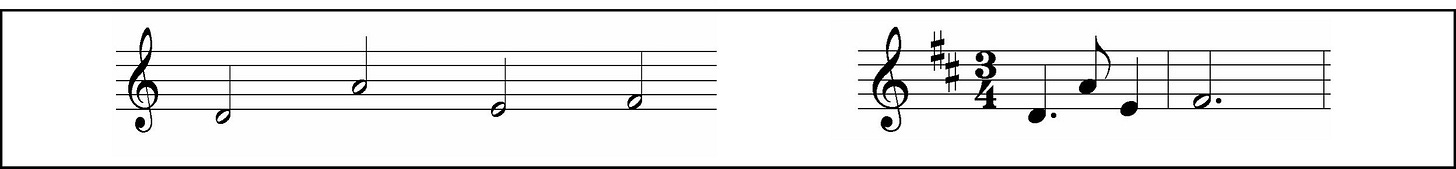

Here, on the left, are the notes a student chose in one of my classes last winter:

On the right are the same notes after “Step 2” — with rhythm added.

Step 2: Decide on a rhythm or timing

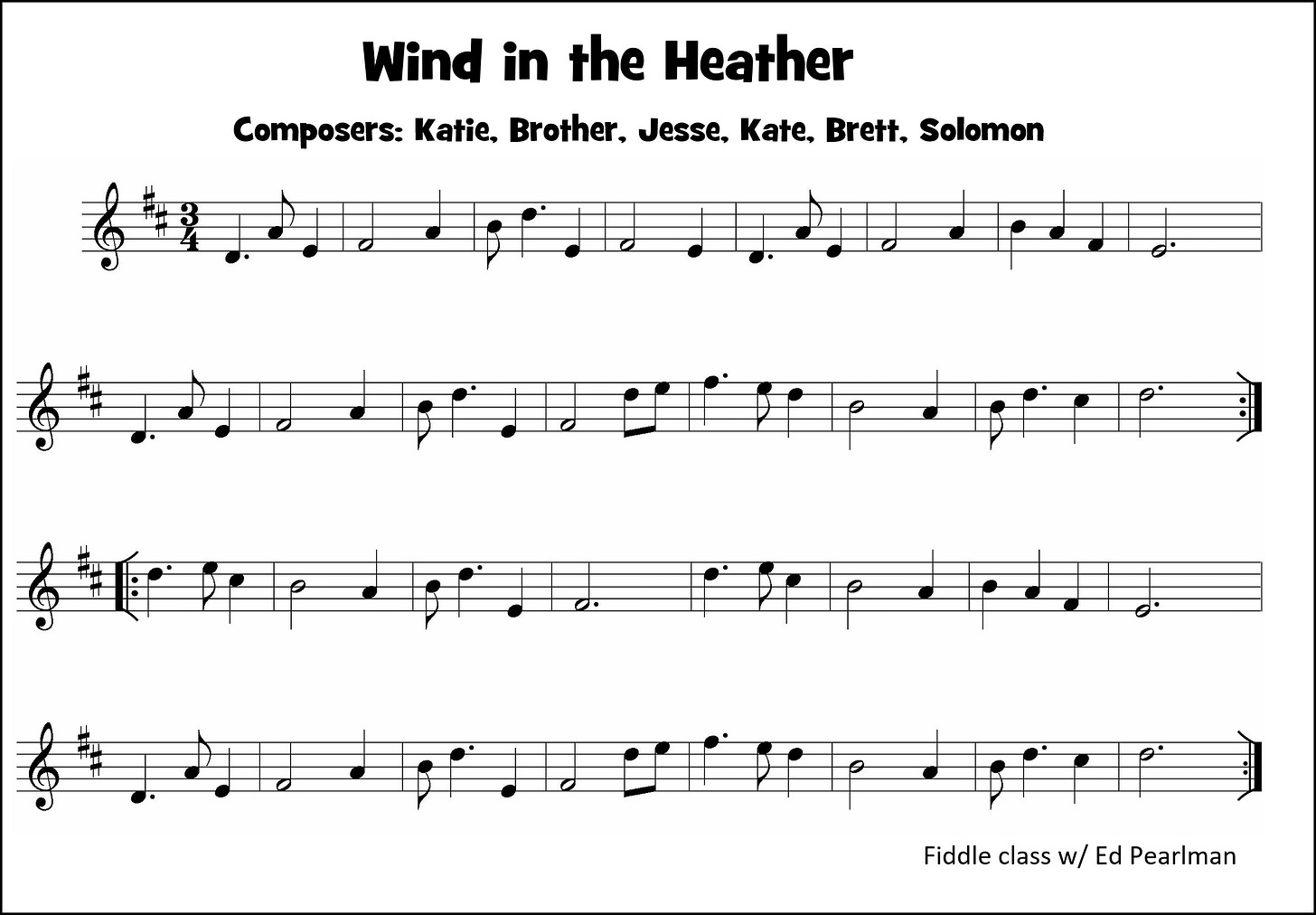

In class, I experimentally played Katie’s four notes back to her in reel time, jig time, as the start of a slow 4/4 air, and as a waltz, to see what she, as composer, might like best. She chose the waltz timing, probably because we had just been learning a waltz and it was in her ears. In fact, the waltz was in the key of D, and her notes seemed to fit that key too, so we went with that.

The whole trick to deciding the timing is to determine the beat notes. For example, if the second note was the beat note, the first would be a pickup. In our example, she heard the first note as the first beat. The second beat determines the meter.

Step 3: Answer the first few notes

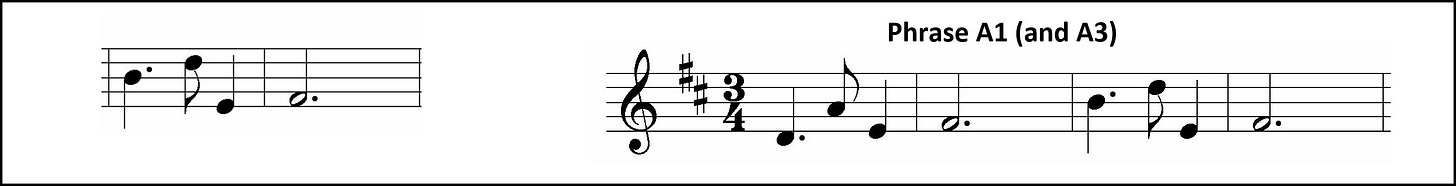

I asked another student, Brother, to respond to the first notes. We already had a waltz timing, so he played these notes in that timing.

On the right is a full phrase, which has four strong beats. Putting Katie and Brother’s ideas together, we had a nice phrase. Since waltzes have one strong beat per measure, (the first beat), a phrase in a waltz is usually four measures. Reels and jigs also have four beats in a phrase, but for them, that adds up to two measures, since reels and jigs have 2 beats per bar.

Step 4: Reply to the first phrase

After playing through the first phrase, it wasn’t hard for Jesse to come up with a response to the first phrase. Most tunes are based on call and response, using some variant of the pattern “Question, Answer, Same Question, Better Answer.”

The Question is our Phrase A1 above (first phrase in the A part of the tune). I suggested starting our Answer with the same notes as Katie had suggested, but following them with something new.

Here’s where I gave the students a target for their Answering phrase. The second phrases of tunes generally do not end on the key note, because that would feel too settled. We want the listener to stay a little unsettled and want to hear more of what the tune has to say. It’s nice to end the second phrase on either the second note of the scale (for this tune, an E in the key of D) or the fifth note (A in the key of D). In this case, we aimed for an E.

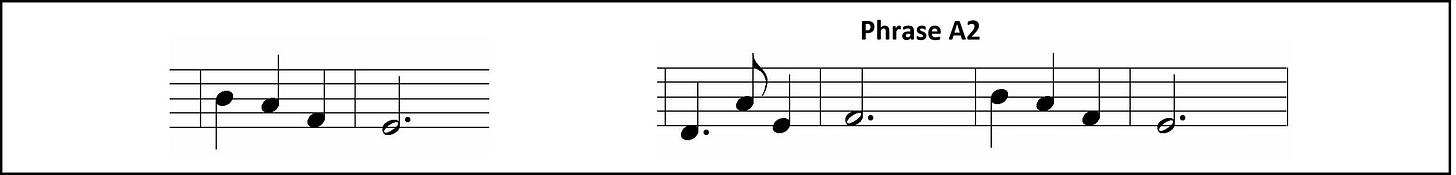

On the left below, is the response offered by another student, Kate (we had a Katie and a Kate), and on the right, I’ve tacked it after Katie’s first idea, to create phrase A2.

Now we have A1 and A2, and can use A1 again as Phrase A3 (Same Question). All we need to finish the A part is a Better Answer — the Ending phrase.

Step 5: The ending phrase, a Better Answer

It’s nice if the ending phrase ends on the key note of the tune, so I suggested we aim for a D. The next student, Brett, jumped to a high note and came down from there, a nice creative move that made for some variety in the profile of the melody. The familiar dotted rhythm of the waltz stayed with us.

Step 6: Replying to the A part

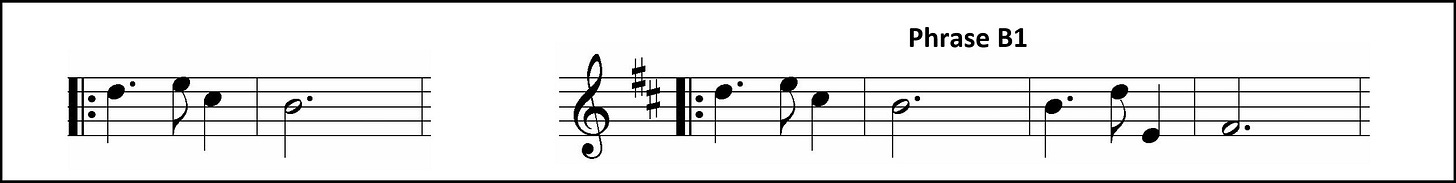

After playing the A part through — A1, A2, A1, End — a few times, students were ready to try a new idea to start the B part. Sometimes B parts will mirror the A part ideas — for example, if the A part starts low and climbs up, the B part might start high and come down. If the A part is jagged and goes every which way, the B part might stick with a few notes close to each other. On the other hand sometimes B parts deliberately take things up a notch and stir up trouble.

In our class, Solomon suggested the following idea to start the B part. It’s just four notes, but provides a change in mood. We paired it with Brother’s idea, which ended the A1 phrase. So with only four new notes, we created a new feeling for the B part.

Step 7: Answering B1

In the B part we are again going for “Question, Answer, Same Question, Better Answer” but we’re going to borrow ideas from the A part for continuity between the parts.

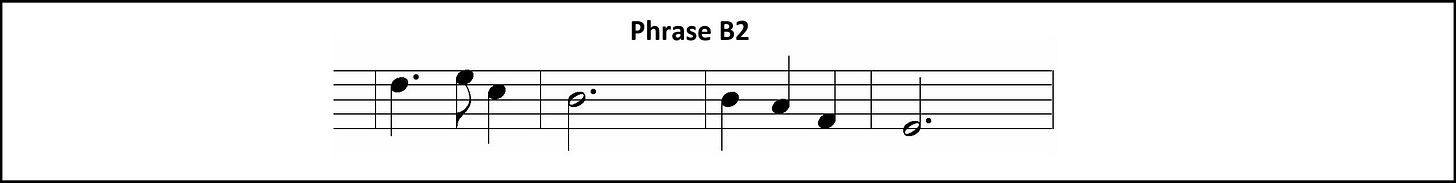

To answer the B1 phrase, we simply started again with the same four notes, and completed it with the last four notes of the A2 phrase. Paralleling the A part, we’re starting B2 the same as B1, and then using the ending notes of A2 to end B2, tying those phrases together.

Step 8: Completing the B part

With only four new notes we were able to create B1 and B2, and we can use B1 as B3, making it the “Same Question” phrase before ending with the “Better Answer.” And why note tie the tune together by using the ending of the A part as the ending of the B part? By structuring the tune this way, we created a whole B part by coming up with just four new notes! Many tunes do this, and to be honest, there have been times when I never noticed how similar the A and B parts of some tunes were until I actually taught them to someone!

Step 9: Adjustments

Once we had all the phrases of our tune, we got to know it by playing through it a number of times, and ended up making a few adjustments to taste.

One adjustment was to add some pickup notes here and there. These are like the conjunctions “if,” “and,” and “but,” which make our sentences flow better.

Most tunes repeat each part, so we can play the tune AABB, which means we could, if we choose, vary the second time through the B part, or could keep it simple and twist the B part as is.

Many tunes will hearken back to the A part before ending the B part. Our class liked this idea, so the B part structure went like this: B1, B2, A1, Ending. Sometimes tunes will only do this on the repeat of a B part, so they use the structure B1, B2, B1, end; B1, B2, A1, end. Other tunes like to throw in a surprise and add a new idea instead of the A1 just before the end of the tune; this is very common with four part pipe tunes, where a whole new idea is often used as the penultimate phrase of the fourth part.

So we added some pickup notes, a rhythm adjustment in a couple places, and we brought the A1 phrase back in the B part.

Step 10: Writing Down the Tune

For a class, I’ll write the tune down for them. For individual students, I challenge them to write it themselves before helping them out. They have to start by playing it and tapping their foot to make sure they know which are the beat notes, so they can determine the meter of the tune. Once you have the beat notes sorted, it’s not hard to fill in the lengths of notes.

Often, a student will write the note values wrong because to them, a note feels longer or shorter than it looks on paper. This is another place (see the comments last week about John Morris Rankin’s tune) where we learn about the compromises that are necessary for writing a tune down to fit its meter and make it readable by others.

Many people, when faced with actually writing a tune, realize that even though they’ve read music for a long time, they never registered how to write the key signature, or which comes first, the key or time signature, or the fact that the time signature only shows up at the beginning. Repeat marks can cause consternation, as we have to make sure all the measures are the right length, but sometimes the pickup notes to the B part are notated on the line where the B part starts instead of at the end of the measure they belong to. And first and second endings are another ball of wax.

Looking at example tunes always helps. However it’s done, in the end, actually writing the tune down ourselves on paper (instead of letting a computer do it!) teaches us a lot that we otherwise may take for granted about how music is written.

Step 11: Naming the Tune

This is the hardest part of all! But it’s fun to consider naming your tune for someone, or for a place, or for an event that happened, based on how the tune makes you feel. One student made up a tune that felt to him like a storm, and after a little prodding, he recalled a storm that blew up when he was camping and had to take refuge in a cabin. He named his tune after that cabin, and now he has a story he can tell about his tune.

In our class, we had a number of suggested titles, and ended up voting for “Wind in the Heather.” Below is the tune; I hope you like it!