We humans love to organize stuff. We have found ways to represent music mathematically on paper because it helps us understand it, even though musical sounds are not all related to mathematical frequencies (see about the harmonic series). As we saw last week, this is true of rhythm and timing as well — and about playing in tune, writing music, or even tuning the instrument.

Let’s look at how to find the beat and the beat notes of a piece of music. Sometimes you need to feel it as you learn and play a piece of music. Sometimes you need to be able to identify it in written music. We’ll talk about both.

Feeling the beat

It is very common for learners to focus so much on playing notes in a sequence called a “tune” that they often don’t think about which notes are the beat notes. But the notes played on the beat are the skeleton of any tune; they provide a structure for the melody. It’s as difficult to understand music without beats as it would be to read this article if there were no spaces or punctuation.

Usually people have no trouble tapping to the beat when they’re just listening, and not distracted by trying to play an instrument. Listen to a recording of the tune and tap along as you listen and enjoy. I may refer to my site at fiddle-online.com here, not to promote it, but because it represents my approach to learning music. Here is a link to a free sample there of interactive sheet music. If you click on the listening track (you can try this with any recording), you can get used to moving or tapping along with the tune because you’re feeling the beat. Do you naturally express this beat with your toe, your heel, your knee, your head, or some other part of yourself? Use that same bit of yourself to express the beat when you learn and play music too. If you have any hesitation about tapping along with music that you listen to, take a look at the article “Step on the Gas” for some good ideas.

If you’re using the fiddle-online interactive sheet music, the next step would be to listen to the recording of just one phrase, using the orange audio button marked “Play A1”. This is a manageable amount of music to get to know. Tap your foot as you listen to the self-repeating phrase. You’ll find four beats in each phrase. Can you notice which notes you want to tap along to? The first note of the tune is not a beat — it’s a pickup note leading us to the beat note which starts the first measure. If you get comfortable tapping along with the music in this way, you can start identifying which notes you are tapping to. Trying it repeatedly with one phrase will build confidence that you can feel the beat consistently, and as you become more confident, you can afford to pay attention to which notes are the beat notes. You can do this by ear, and also in the written music, as explained below.

Once you’re able to feel the beat just by listening to the recording without trying to play on your instrument, try playing only those four beat notes in time to the recording. Let the other notes go for now. From here you can begin to add other notes, maybe only one at first, then another, all the while making sure you keep playing those four beat notes in time with the recording. This way you can build up a phrase starting with the foundation — the beat notes.

Your bow is your beat machine, while your other physical movements (tapping foot, knee, etc) are your physical backup system. Keeping the beat in your head isn’t good enough; your head is easily overwhelmed with other tasks! Play the beat notes with a consistent bow direction to give your beats power to spare — one good goal is to start each measure with a downbow. You may have to slur some notes on the same bow in order to do this, but if you concentrate on the upcoming beat being a downbow, the other bowings come naturally. The goal is to feel the beats with your bow, not to memorize or write down a bowing pattern. You’ll find that in reels, each beat can be downbow, whereas in jigs, the first note of each measure can be downbow and the second beat of each measure upbow. If you bow consistently, your bow hand can guide you through a tune more than you might think.

Once you feel comfortable bringing out the beat notes, you’ll find that the other notes are far easier to fit in place than they would be if you simply tried to play them all in sequence without playing them in relation to the beat. The beat notes give all the notes a home.

One surefire method of feeling the beats is by using or writing lyrics that naturally match the rhythm of the tune. It’s fun, too, and nobody else has to know how silly or bawdy your words are!

Finding the beat in written music

You can count on the fact that the first note of each measure is a beat note. As a general rule, play it downbow. It’s the second beat of each measure that can be trickier to find in written music.

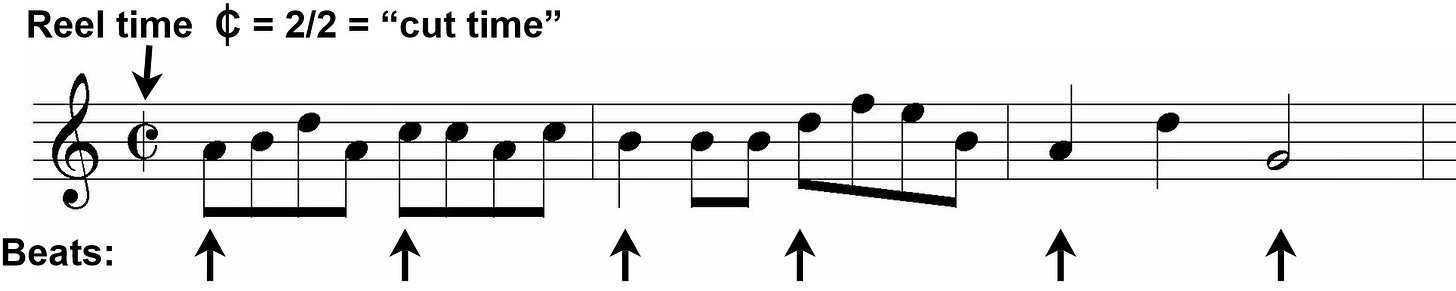

In a reel, there are two beats in a bar. Some people mistakenly write reels in 4/4 time, which confuses people into thinking there might be four beats in a bar, whereas reels are played with two beats in each measure. Each beat has the equivalent of 4 eighth notes. If written out properly, the eighth notes should be grouped into fours by dark lines (beams) connecting the stems. This makes it easy to see the beats, because the first note of each beamed group of four is the beat note. Sometimes a beat will contain one quarter note plus two eighth notes (beamed together as a pair). If a measure does not have all eighths, get used to seeing each quarter note as worth 2 eighths. A quarter + 2 eighths = a beat. Similarly, 2 quarters = a beat.

Whether or not you are a fan of math or counting, you can and should always feel the beat physically, both by moving your bow, and some other part of you that likes to move (foot, heel, knee, whatever you naturally use when you listen to music and move to it). If you tap your foot to a reel, it will come down on each beat (a half-note per beat = 2 quarters = 4 eighths). And just as an orchestra conductor has to lift the baton in order come down on the beat, your foot also has to lift before coming down to tap on the beat. The upswing of a baton or of your foot is the anticipation of the beat, like taking a breath before you speak. If a bar of reeltime is in 2/2 (cut time), then the beat goes 1 & 2 & 1 & 2 & with the foot coming down on the beat and up on the “&”.

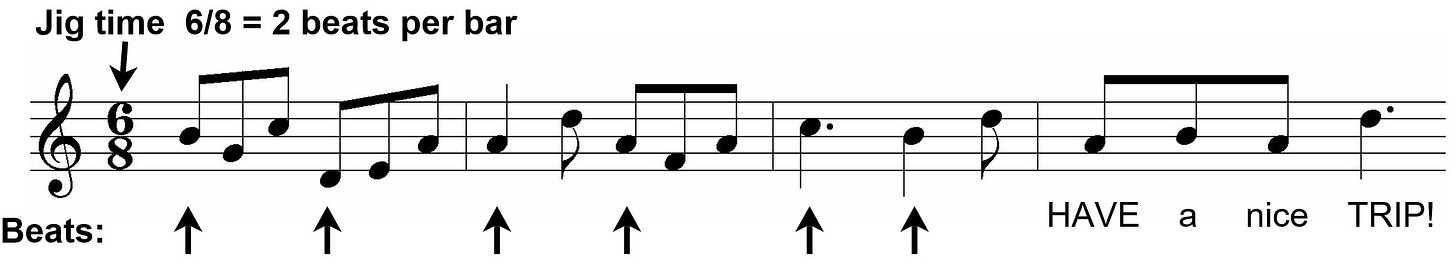

Both reels and jigs have two beats in a bar — often two per second, the same as is common in languages worldwide (see the article about dyslexia and music). In reels, each beat has 4 eighth notes per beat (an even number) while the jigs have 3 eighths per beat, a triplet (an odd number). These are written beamed together so you easily see groups of 3, and you can be sure that the first note of the group is the beat note. There are two other common patterns within beats in a jig. One is a quarter + an eighth, and the other is the dotted quarter, a single note which is equivalent to 3 eighths, and takes up a whole beat. Again, writing lyrics can help you get the feel of a jig, as in “HAVE a nice TRIP” where the capitalized words are the beat notes. HAVE + a + nice would represent a triplet (one beat).

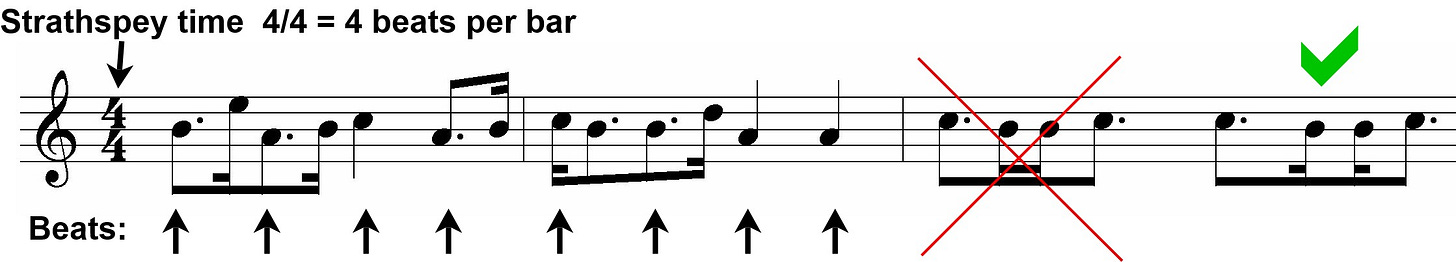

Strathspeys have four beats in a bar. Beat 1 is always the first note of the bar, and each beat is equivalent to a quarter note, or two eighths. A dotted eight + sixteenth is also a beat (sometimes the sixteenth comes first).

The red X illustrates a common problem with music software — when there is a group of two beats, the first using dotted eighth + sixteenth, and the second using sixteenth + dotted eighth, computers will often beam the middle two sixteenths, which makes it hard to see the beat (it’s the second sixteenth note). This pattern should be written as shown above under the green checkmark. Music software can do this if the user knows how. This way of writing it makes the beats much clearer because the third note belongs in a beat with the fourth note, not the second.

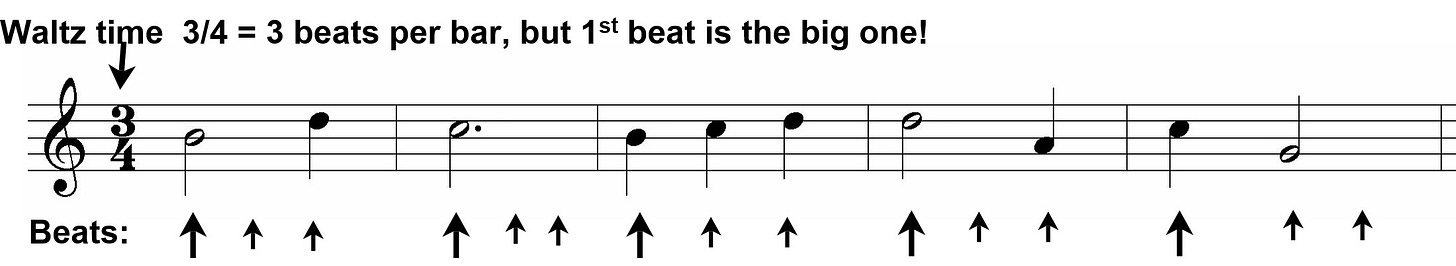

Waltzes are in 3/4 time but only the first note in each measure is the strong beat. The other two quarter note beats are weaker, just as in the dance, where you take a big step on beat one, and collect yourself with small steps on beats two and three of each measure.

Slow airs and marches are functional tunes and can be written in various time signatures. As you may know, the top number in the time signature will tell you how many beats there are per measure, while the bottom note tells you which type of note gets the beat. There are exceptions to this, though, as we’ve seen in the quicker tunes, where jigs are written in 6/8 (divided into two beats of 3 eighths each) and some reels are written out in 4/4 even though theyre played with two strong beats per bar. I always write reels in 2/2 or “cut time” (sometimes written as a C with a line through it).

Probably the trickiest kinds of beat to play are the ones that don’t have their own note to mark the beat. This happens when there is a longer note that crosses over a beat. To play this, you have to feel the beat even though you don’t change bows or play new notes with the beat. Next week we’ll talk about this in an article called “The Beat Not Played.”