If you enjoy these articles, please pass the word to others who you feel would get something out of them! Feel free to place links in social media, or if you’re viewing this online, you can highlight some favorite lines and “restack” them, which places it in Substack’s Notes for all to see.

Many players want to learn music by ear but feel daunted by it. Classical music requires people to read music, and has generally dominated the way people learn to play instruments. Reading is a great skill useful to all musicians, but it’s really a different mind set than learning and playing by ear, which is in itself incredibly helpful to all musicians.

Once you can read music, it’s pretty alluring and hard to wean yourself from. There have been times when I was playing from sheet music for a tune I knew well, and still found it very difficult to break away to simply play the tune. The switch requires an adjustment.

When reading, music tells you what to do. It’s a little like using GPS — you know you’ll get where you’re going but you may not remember how you got there. You’re not likely to feel confident about getting there again with directions. But when you learn and play a tune by ear, you also take note of and learn all the landmarks. You think in phrases, patterns, structures. You’re ready when phrase A1 comes back again; you know the shape of the ending phrase and get to the beat notes even if an in-between note or two doesn’t cooperate.

There are many elements to learning by ear — timing, tune structure, note patterns, and more. These are what music is all about, what it’s trying to say. This is why playing by ear tends to be more musical. Even classical soloists play by ear. It’s like the difference between listening to a speaker read a speech out loud vs one who just talks to you. Some of these elements of playing by ear have been explored in earlier articles, so I plan to summarize them in a later article with links.

Just now, we’re going to address one aspect of learning by ear — something I call “ear mapping.” I’m going to talk about it as a fiddler but these ideas apply to any music and any instrument, or the voice.

Learning a tune starts with the ears. This might be a bit of a mind-bender for some to consider, but really, it’s the ears that teach the hands. The brain won’t admit this, but its job is really to observe and take notes for next time; it doesn’t actually know enough to tell everybody what to do (shhh, don’t tell it). Of course, that doesn’t stop the brain from trying to give orders and get in the way. The eyes, meanwhile, do their best to look super important, but there’s not much they can do when it comes to playing fiddle — music is about sound, and playing the fiddle is about muscles; the eyes can’t even see what’s going on, being farther apart than the strings, and at a weird angle. This is a big comedown for the eyes, who are totally dominant when it comes to driving, reading, using a computer, and generally helping us navigate through every day. For more on this perspective, read the article about “Reversing Old Presumptions“.

But here’s the rub — we tend only to think about things that we can verbalize. We have a hard time thinking about the work of the ears and hands because we hardly have any words for what they do. What learners think most about, and therefore work hardest at, are concrete tasks, usually ones that their eyes and brains can direct — for example, the notes on the page, music theory about names of notes, keys, marked bowings. We mistakenly imagine that our brain sits at its desk and orders the fingers to play this note and that one, and commands the bow to move so we can hear the notes.

This is all very unfair to the real workers — the ears and hands. When you make a mistake, don’t get mad at your brain for screwing up. Thank your ears for knowing what the music should sound like and alerting you that they want to hear something different than what you played. Even a total beginner’s ears can learn a group of four notes after hearing them twice, even if the beginner can’t quite play them yet.

Maybe if we devise some useful words about the ears and muscles, we could use them to better direct our thoughts.

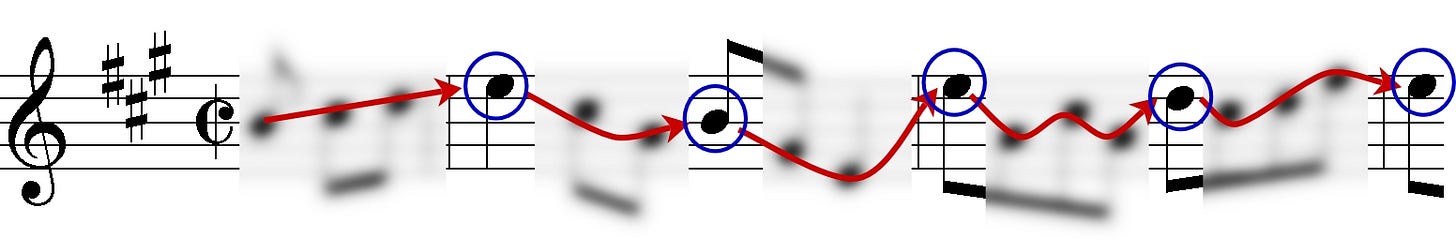

Let’s start with the words “ear map.” When you listen to a tune you’re learning to play, your ears map out the tune. Since in order to read this article, you have to use your eyes, let’s use a visual analogy. Here is how the ears might start to “map” a tune to get a handle on it:

We hear the important notes in the context of the beat they land on. We feel the pulse and how it matches with the beat notes. The pathway getting us from one beat note to the next is at first a blurry one; we don’t yet know the details. We want to know where we’re headed first, then we’ll learn how to get there.

In fact, if you play those beat notes on time, even if the notes in between only approximate the ups and downs of tune, you will be playing that tune. But if you change the notes that land on the beats, you’ll be playing a different tune. Changing only the in-between notes, the pathways from one beat note to another, comes across as improv! (See “All Music is Improv”)

There are often only four beat notes in a phrase; it’s a manageable amount of music to learn. The phrases are the building blocks of the tune. The beat notes and phrases create an outline that allows you to organize your understanding of a tune, and play it more naturally and musically.*

Next time you want to learn a tune, see if you can think about mapping it out with your ears. Rather than analyzing the map, try to recognize and anticipate the beat notes. Feel them with your body by moving, tapping, marching, or walking as you listen. Remember, music without timing is just sound.

Occupy your mind with bigger things than the notes you might see on a page — sense the phrases, just as you would hear complete sentences when someone’s speaking to you. Notice the order of phrases and when they repeat — many tunes are structured as Question & Answer, then Same Question & Better Answer. Note how you feel about the high and low points, where you sense simplicity and where complication, where the music seems comfortable and predictable, and where it surprises.

Demand more of your ears and hold them accountable as you work on a tune. Rather than play through all the notes as if checking them off a list, ask yourself some questions related to how well you listen — Did you allow your ears enough time to map the music? Are your ears hearing all the beat notes? Are they comfortable with the timing? Did you let your ears sense the profile of the music, the ups and downs, even if some of the specific notes are fuzzy? Those humble little listening holes in the sides of your head are doing a lot of work. They will reward you well for paying attention to them!

Give yourself a frequent break from the quantifiable — the written notes, the finger numbers, note letters and rules — and let your ears be your guide. If you allow your brain a vacation from being in charge, it will observe, take notes, and may well notice some pleasant surprises!

And you’re likely to find yourself learning a tune faster than you expected, and retaining it longer.

——

*If you like this way of approaching music, you might be interested in the way I’ve developed it on fiddle-online.com (there’s a free sample linked in the big red box), where every tune is marked by phrase (with colored boxes), accompanied by self-repeating audio by phrase, as well as a listening track for absorbing the overall feel of the tune, and a moderately-paced playalong track, to build the tune by placing those phrases where they belong.

Love your comparisons between reading music and playing by ear. I waited far too long to take this transition on. It is EXACTLY GPS- you lose that signal and you're pretty much helpless...plus it made for a nice segue into your Playing in a Session piece. No way can you bring a portfolio of sheet music with you to the session.