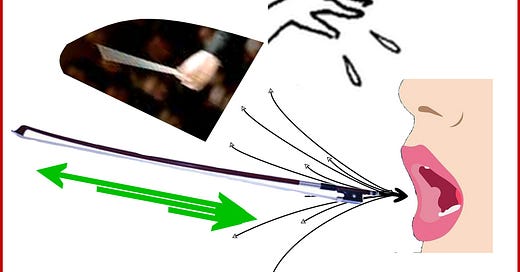

Although this is, like some others earlier, a violin/fiddle exercise/game, I’ve heard from some wind instrument players, accordionists and singers that when they translate bowing ideas to breath, they find these ideas thought-provoking. I hope this game proves of interest and use to you. (I like call my exercises “games” because exercises tend to be thi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Essays On Music & Learning Fiddle/Violin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.